Two hundred years ago the wooded acres on the south edge of town we now know as The Grove was then called Indian Fields, and was a large expanse of woods inhabited by Potawatomie tribes. As the white man moved in and the Indians were forced off their land to make room for “civilization,” one white settler by the name of Lyman Barnard showed up here in Berrien Springs. He originally came to Michigan in 1828, and probably to Wolf’s Prairie (as it was then known) a couple years later. Biographies of him note that he was brought up among the Indians and that he was one of the only white men the Indians trusted. It’s only fitting, then, that he should become the caretaker of the Indian Fields park, which would later don his name.

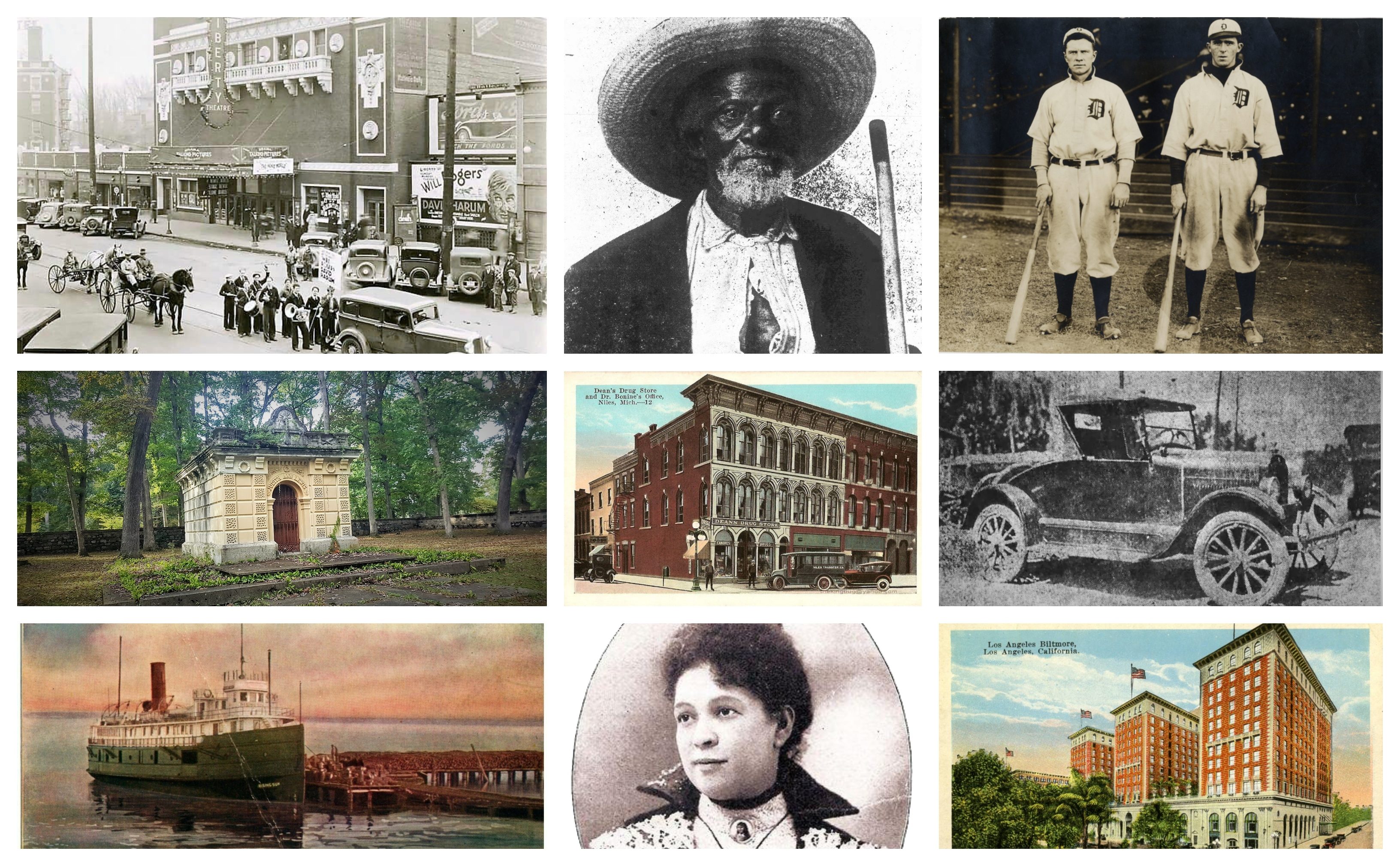

Barnard’s story didn’t begin in Berrien Springs, however. He was born In Cayuga County, New York to Roxanna Gardner and Elisha Barnard in 1807. According to Find a Grave, his grandfather Moses Barnard was a Revolutionary War veteran who fought in several campaigns, including the Battle of Bunker Hill. Young Lyman also had adventure in his blood, as he ventured west as a young adult. First he went to Venice, Ohio ,and by 1828 he found his way to the Pokagon prairie in Cass County, Michigan. For the next couple years, he sailed a boat called the Dart, which he built himself, across Lake Michigan between St. Joe and Chicago. By 1832, he settled permanently in Berrien Springs.

In 1838, he married Susan Brown, sister of Pitt Brown, another of our town Founders. They had a daughter, Susan Aurelia, later that same year. Susan A. would go on to marry Captain Darius Brown, who was a decorated veteran of the Civil War, of the 12th Infantry.

By 1847, Lyman became a practicing physician “not so much from choice or a desire to make money as to alleviate the sufferings of his neighbors,” as it was stated in Volume 4 of the Pioneer Collections Report of the Pioneer Society of the State of Michigan, copyright 1906.

Dr. Barnard also served as Postmaster during the 1860s and during the turbulent times of the Civil War, he turned the second floor of the Post Office into a drill hall for members of the abolitionist society. In an article from 1998 in the South Bend Tribune, historian Robert Myers describes the animosities that existed, sometimes even between families, over whether or not the cause of the war was just.

In 1874, he teamed up with Dr. Frederick McOmber to publish the Berrien County Journal. McOmber eventually sold Barnard his interest in the paper and began a new paper called The Era in 1876, before selling his interest in the Era to the Benson Brothers (George R. and Dewey M) in 1901. Eventually the two papers merged to become what we now know as The Journal Era.

Around this time, Barnard began potting around in the Indian Fields, cleaning up and even building a log cabin on the property, with the help of Thomas Marrs, that would eventually become his museum of Indian artifacts and other curios. Due to his upkeep, the park eventually became known as “Barnard’s Grove” and it wasn’t long before picnics and gatherings were being held there on a regular basis. The two biggest gatherings were the Old Settlers Day and the Young Peoples’ Picnic. Old Settlers’ Day began in 1874, celebrating the area’s pioneers and their families. Glee clubs came to sing, brass bands came to play music, great feasts were held, and long speeches were given, and transcribed in local papers. At the 5th annual picnic in 1879, the weekly Palladium boasted that there were 6,000 visitors. By 1881, the crowd estimate was 7,000. Old Settler’s Day eventually became known as known as a more politically correct term, the Pioneer Picnic. The Pioneer Association became so important to Lyman Barnard that he bequeathed to it the use of his grove for 18 years after his death.

Meanwhile as the elderly citizens were celebrating the past, the Young People’s Picnic was investing in its future. The first Young People’s Picnic was in 1877 and it was soon moved to the Grove. The annual event was much anticipated around the county. Membership dues were twenty five cents, and anyone under 35 could join.

In 1881, Barnard died just a few years after the death of his wife. The Pioneer Association memorialized him with a lengthy tribute to his life as, “our grand old patriarch, the father of our society, the kind neighbor and true friend.” They went on to remark that “in politics he held decided views well known to all yet he could respect the opinions of those who differed from him and discuss those differences in candor and fairness.” He is buried in Rose Hill Cemetery on the edge of town.

It’s only fair to point out, despite the Pioneer’s memorializing, Lyman Barnard wasn’t completely free from controversy. As any newspaper editor will tell you, avoiding negative press yourself is a lofty ideal. In 1875, Barnard was arrested for libel against the editor of the Niles Democrat. And the year before that in 1874, Barnard got in a fight over politics with Major George Murdoch, resulting in a couple punches taken to the ear, and some bad press to boot.

After Barnard’s passing, the village of Berrien Springs purchased the Grove’s ten acres of property from the Platt Sisters for $922. When the Interurban Railroad Company leased the land, they planned to build a hotel nearby but the lease fell through soon after and in 1908 the park was reduced in size after the creation of the dam flooded the part of the park once used as a horse track.

In 1916, the village hired Charles Fischer to maintain the park and build the area into a resort. He built a bandstand, a pavilion, and added cottages to the west that we now know as Fischer Court. There was once a campground, docks with boats to fish the lake or swim, shuffleboard, a bathing house, and even a shooting range.

According to an article from 1988 in the South Bend Tribune, darker days were ahead. Sewage took over the lake so it became unfit to fish or swim, and the Interurban Railway ceased operations in 1934. Gradually the Grove grew quieter with the passing years but it was still occasionally used for picnics and gatherings. In 1984, a tree fell on the pavilion and according to Myer’s “Greetings from Berrien Springs” book, the insurance settlement helped fund the modern bathroom facilities we still have to this day, although Covid has recently closed them. A large playground structure was also added in the early 2000’s called Wolfs Prairie Playground.

And about that historical marker placed on the bluff by the Berrien County Historical Society? Unfortunately it’s not accurate. While Barnard found Indian artifacts on the land, there is no confirmation of the park being anything more than Indian campsites. Historians now agree that there was never a Jesuit Mission or French Fort situated on the land there either. Archaeological digs have found no evidence there ever was one. According to one county history book (History of Berrien and Van Buren Counties, 1880), Joseph Feather, an early carpenter in the village, claimed that a Mr. Wilson, captain of a keelboat on the St. Joe River, was interred at Indian Fields. But so far his bones have not been found.

So the next time you’re enjoying an afternoon at our village’s oldest park, be sure to take a moment to remember the man who made the park possible. Pick up a twig or two in Lyman Barnard’s honor and keep your eye out for some cool Indian artifacts, or even better yet… the bones of Captain Wilson.

Can’t get enough of Berrien County history? Join my Berrien History patreon for even more research:

patreon.com/berrienjen

Thanks fir the great article. Iive kiddy corner west on Park and aporeciate the Park everyday.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember that the boy scouts had meetings there in the 1960s, any information on the island north of the dam

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thankyou for this informative article. I’m so very happy to hear any information of our quaint little town!!

LikeLiked by 1 person